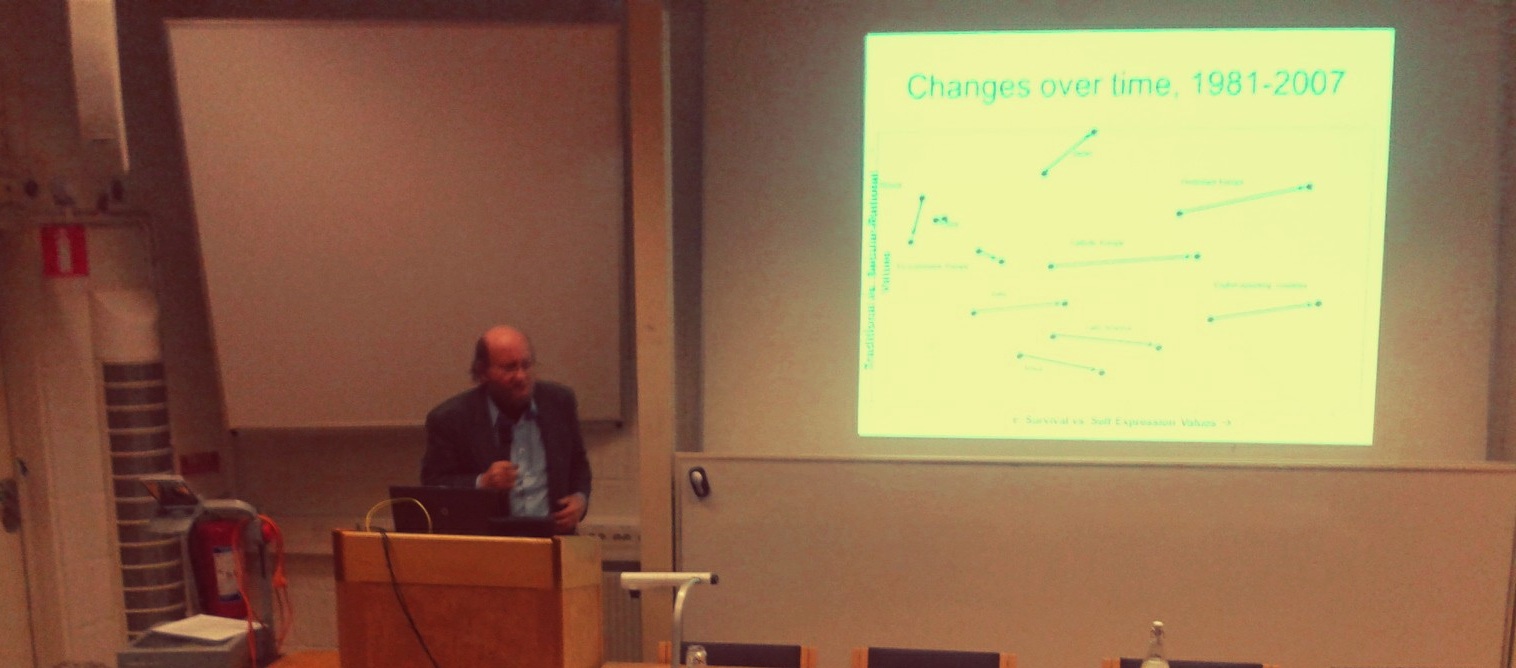

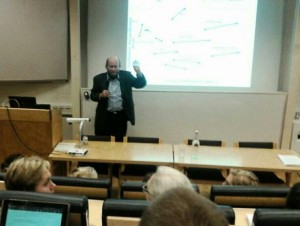

Ronald Inglehart, Professor in Political Science at University of Michigan, gave an open lecture on “Evolutionary Modernization and Social Change” at University of Gothenburg in 21st November 2012. In connection, Utblick’s David Westerberg met with him to discuss issues of politics, religion and secularism.

Q: Is religion an independent variable?

Inglehart: Yes. I would say yes because religion has been around for a long time. It has autonomy, it is clearly shaping things, and my cultural analysis indicates that having a Protestant, Catholic, Islamic or likewise heritage is a strong predictor of all kinds of values.

Q: Is it not problematic to identify and analyze religion as independent from politics or economics?

Inglehart: No, I think that we can measure religiosity empirically, first of all by what denomination people belong to, and secondly by how important religion is in their life. That is actually a very powerful predictor of attitudes because you can predict a whole range of other attitudes from those two things, like their stand on abortion, divorce, homosexuality, child upbringing, and so on, so there are all kinds of things linked to religion. When people do not think religion is important it usually predicts the opposite set of things, so the fact that religion is unimportant is itself a powerful predictor.

Q: Do you see any problems with translating the term and concept “religion” to non-English speaking cultures?

Inglehart: I hate to be simplistic, but no. The concept of religion is almost universally recognized.

Q: But surely measuring religion in different cultures must be dependent on what concept one uses and what it means in that context?

Inglehart: It’s not entirely unproblematic, but I would say that this is one of the things that are more or less universal, that religion is almost universally recognized. Even if you don’t like it you know what it is.

Q: During your lecture you referred to Marxism as a ‘belief system’. Do you see any overlapping between religion and political ideologies?

Inglehart: Very much. I think that Marxism was a secular religion, and it went to great lengths to repress religion since it was a competing belief system. As long as people believed in the Russian orthodox faith they weren’t good communists, since they had to believe in the whole worldview of communism which actually, in some ways, was modelled after Christianity, especially the notion of a judgement day, when history will end, the good will triumph and the revolution of proletariat will be the last trumpet blowing, and so on.

Q: What about political ideologies in general?

Inglehart: In extreme forms, it sometimes claims to have absolute truth, which, in my view, is always wrong. In politics absolute truth is usually a balancing act between too much of one thing or too much of the other thing.

Q: To what extent do you view the separation of religion and politics an ideological function of the state?

Inglehart: Traditional religions claimed to have the absolute truth in all spheres, and traditionally the Catholic Church claimed the right to define and legitimate political authority. It became compatible with democracy only when it gave up that claim. I think democracy necessarily does not claim absolute truth. It is, in my view, a very modest claim: whoever wins the election has the right to rule.

Q: How should we understand the concept of “secularism”? Is secularism an ideology?

Inglehart: It can be an ideology. For example, the Soviet version of secularism was an enforced ideology. In the United States the separation of Church and State are pushed to an extreme by some people where it would be wrong or even criminal to mention God or have prayer in schools. That would be a kind of secular ideology in my view. Extreme secularism can be totalitarian; some totalitarian states force secularism on people just like some totalitarian states like Iran force religion on people.

Q: How does democracy as an ethos, whether religious or secular, accord with the political system of the state?

Inglehart: In a very general sense every state depends on some belief system. I think every state, if it persists for any length of time, has a legitimating myth. Any social order requires an underlying belief system. That is, any political order, if it’s going to be stable and persist rather than simply be based on naked force, needs a legitimating myth. A warlord may come around and be able to get things simply by pointing bayonets at you, but any state that persists for a long time has some legitimating myth. By myth I don’t mean that it’s false, but simply that there is a set of beliefs which is supposedly rooted in deep history which indicates that this is the right way to rule, or this is the right way to choose your rulers, whether it is because God gives divine right to Kings or because elections are almost holy. In the United State, and I suppose in Sweden too, children in primary school are brought up with some reverence with democratic institutions, which then helps to support them.

Q: Does the democratic ethos necessarily depend on the state, or the other way around?

Inglehart: Generally democracies have a strong national myth. It can be things like “we are a great democratic country” and being proud of democracy and social institutions; although Swedes are probably proud in a more subtle version than Americans, they nevertheless share this. I think that any society draws on a sense group of group cohesion which may be nationalism or class conflict, or even racism. But to get people to rally behind you, I think you need some kind of unifying story.

Q: Could the political system of the nation-state undermine democracy?

Inglehart: I think the ideal notion of democracy might not require any coercion, but in reality any society requires some measure of coercion. If you have criminals, you have to deal with them.

Q: Do you see any similarities between belief in religion and belief in the nation-state?

Inglehart: Oh yeah, sure, it is certainly similar in some ways, especially in terms of “the righteous in-group” vs. “the unrighteous outsiders.”

Text: David Westerberg

Very interesting, great interview!