Before I left for Sarajevo in Bosnia-Herzegovina with UF, we decided that I would write an article about the trip for Utblick. When I asked whether the editors had a specific topic in mind, they said it was completely up to me. Initially, I thought I might do a piece on the peculiar mixture of religions and cultures found on these crossroads between East and West, or perhaps I could report about the international institutions we would be visiting.

Now that I’m back from Sarajevo, I know that this is not what struck me the most. What left the deepest impression on me is how incredibly, heartbreakingly present the Bosnian war still is. Both in space and time, this city still breathes, talks and mourns the atrocities committed between 1992 – 1995.

Granted, Bosnia-Herzegovina is taking small steps in the right direction (however few and far in between, as highlighted by talking to the hardworking yet disheartened representatives of Transparency International and the EU delegation). But sometimes it feels like this country is still right in the middle of dealing with the past, when not a day goes by without newspapers publishing something related to the war, when the majority of war crime perpetrators walk free, and when cemeteries are strewn around town – their gravestone inscriptions all ending in a similar date.

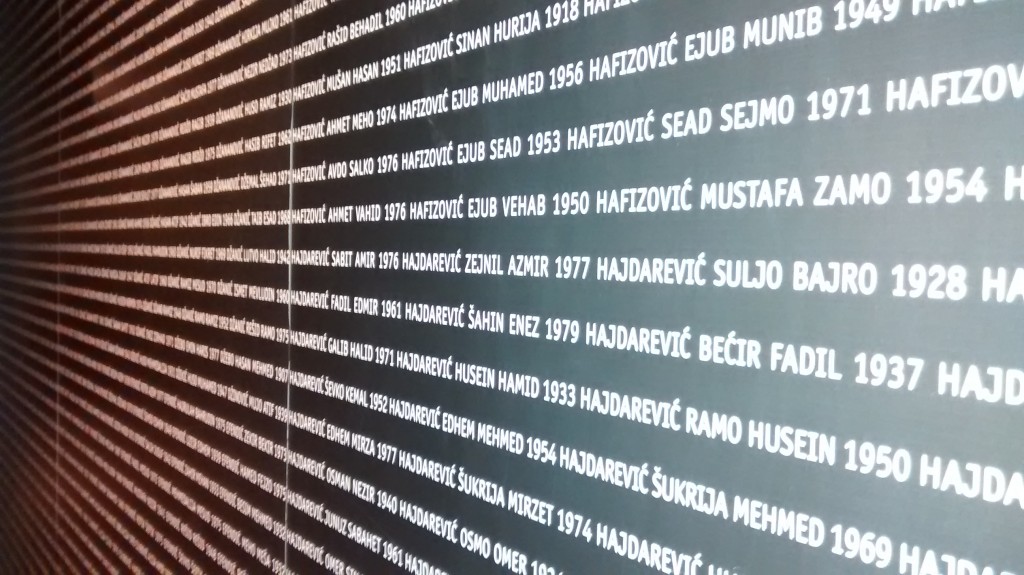

During our first day in Sarajevo, we strolled around happily in the city center – seeing the sights, basking in the sunshine and enjoying that content freedom that comes from being on holiday. Near the main cathedral, we discovered a gallery with work by a Bosniak photographer, Tarik Samarah. Called “11/07/95,” the gallery is dedicated to the Srebrenica massacre that occurred on that very date, and consists of photographs of the survivors (mostly women and children) and their lives afterwards, as well as of the work of identifying and burying the bodies found in mass graves. A group of about eight of us visited the exhibition that day. Upon entering the elevator, we were met by the words You Are My Witness (in Bosnian/Serbo-Croatian, Turkish and English) on the mirrored interior. When the elevator doors opened again, a 16m long wall faced us with what at first seemed to be a white alphabetic pattern. A closer look stunned us into silence. In front of us were hundreds of thousands of names, all belonging to the victims of the Srebrenica genocide.

Before we looked around the gallery, we watched an introductory documentary about what happened in Srebrenica. In the early nineties when Yugoslavia fell apart and its constituent republics started declaring themselves independent, Bosnia slid into a civil war between its three official peoples (Croats, Serbs, and the Bosniak Muslims). The Bosnian Serb army (supported by Serbia and the ex-Yugoslavian army) swiftly attacked and took over large swathes of the country, especially in eastern Bosnia. What ensued were some of the worst war crimes committed since WWII, including ethnic cleansing, mass rapes, terror, genocides and concentration camps.

Cut off from other Bosniak areas, the village of Srebrenica near the Serbian border quickly became a haven for refugees at the start of this civil war. As more and more people amassed in the area, Srebrenica started suffering from severe food shortages and humanitarian problems. Amidst a deteriorating crisis in April 1993, the United Nations officially declared the village a “safe zone” in the war and demanded that all parties gave up their arms. In return, a couple of hundred Dutch peacekeepers were stationed in Srebrenica, promising to keep the villagers safe from harm as the Bosnian Serb army drew closer and closer.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=QfInjlNoT4Q

(Radko Mladic entering Srebrenica triumphantly)

Things went horribly wrong on 11 July 1995 however, when enemy troops under the command of Radko Mladic (currently on trial in The Hague) finally entered and took over the town. In a desperate search for protection, over 25 000 people attempted to seek shelter in the UN compound. Chaos ensued when all but 5000 of these refugees were shut outside the gates for lack of space. Another 10 to 15 000 men and boys fled through the mountains instead, trying to reach other safe areas out of fear of what would happen to them if the peacekeeping protection failed and they would fall into Bosnian Serb hands. Outside of the UN compound, the Bosnian Serb army slowly started separating the remaining men and women from each other – disturbingly aided by some of the Dutch troops. Over the course of the next couple of days, an estimated 8372 of these people were captured, transported to nearby fields, sports halls and factories, and brutally slaughtered there.

The oral histories of the victims were amongst the most painful things to watch, as mothers, wives, daughters and sisters described the last time they had seen their son’s face; how they could still feel the touch of their husband’s hand on their shoulder when saying goodbye; or how they still don’t know what happened to their brother when he fled to the mountains. After the film had finished, more than half of us were crying and none of us said a word.

Until this day, mass graves keep being found in Bosnia almost every year. The fact that the perpetrators often reburied victims from a primary grave into a secondary or even tertiary grave, has created a situation in which victims’ remains may be spread over a vast area, making it extremely difficult to identify exhumed bodies. Family members often wait for years to find out what happened to their loved ones, sometimes dying themselves before ever learning the truth. On 11 July every year, a collective funeral is held for victims of Srebrenica, though only for those of whom at least 70% of the remains have been found. Last year, more than 400 graves were dug, including one for a baby of only a couple of days old.

(Do take a look at the haunting pictures exhibited at the 11/07/95 gallery: http://tariksamarah.com/thumbs.htm

The photographer’s website also includes an account of the Srebrenica events, but be warned that it includes violent details of what happened: http://tariksamarah.com/genocide.htm.

For more on the gallery itself, click http://galerija110795.ba/en/)

When we walked out of the museum, blinking into the suddenly harsh sunshine, none of us really said anything and many rummaged through their bags in search of handkerchiefs.

The first thing my eyes now noticed were no longer the people having an ice-cream in the shade, but the walls of almost all of the surrounding houses. Still now, over twenty years later, they are riddled with bullet holes as scars. Walking back to our hostel through the center, we passed several “Sarajevo roses” on the pavement. Like blood-red rose petals splattered eerily across the street, these roses are spots where one or more inhabitants of the town were killed by mortar shelling during the siege of Sarajevo, the remnants of which were later filled with resin to mark the place.

A couple of nights after our visit to the Srebrenica gallery, I met up with a Bosnian friend of mine that I had studied with in Japan some years earlier (and who requested to remain anonymous). At the time, I hadn’t asked him much about his experience of the Bosnian war. Now, after gaining so much new knowledge and impressions from our visits to the War Tunnel museum, the International Criminal Tribunal for Former Yugoslavia and the Srebrenica gallery, I asked him to tell me about his life during that time.

When the war started in 1992, my friend was a boy of 13 years old. For the entire duration of the war he kept living with his family in Sarajevo, which was under heavy siege by the Bosnian Serb army from the mountain edges around the city. Laughingly, my friend told me that the initial reaction of him and his classmates had been one of joy: now they wouldn’t have to go to school anymore! (That was the case for the first year of the siege. Later however, teachers would travel to the different neighborhoods so that schoolchildren could still be educated without having to risk getting hit by enemy fire when walking through town). Suddenly though, things changed drastically. A year before, my friend had still gone skiing happily in the winter with his parents and his main desire was getting a new Gameboy. Now, there was no water, no electricity, and the family slept with all their clothes on because of the cold. Once or twice a week, my friends and the other kids from the neighbourhood would walk an hour into town to get water, dragging the 50 liters all the way back to their families. In the meantime, the Bosnian Serb army continuously shelled Sarajevo, threw mortars and hit buildings. Snipers with machine guns were placed on strategic highpoints, creating terror amongst the inhabitants. A trickle of humanitarian aid from the UN and the Red Cross reached the city, although my friend said that some of the canned food was so appallingly bad that maybe, only maybe, would he consider giving it to his dog today. When I then assumed he had gone hungry all the time, he was quiet for a while. “In a way, we were healthier than we are today,” he answered.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=-boLmzBnzO8

(Video footage of the siege of Sarajevo)

When I asked my friend how on earth he managed to survive, he told me that life had carried on: he played with his friends, they joked and sometimes laughed until their stomach hurt. And everyone kept saying “Next month. Next month for sure, the siege will be over,” as the war dragged on and turned into years. Paradoxically enough, my friend’s main conclusion was that he had been lucky: in the beginning of the siege, their house had had a vegetable plot that supplied them with some food; no one in his near family got killed; and most importantly of all – they had not had to endure what others in occupied eastern Bosnia had to suffer. With a tone of sadness and horror, he described how the war crimes committed in that part of the country contained cruelty literally beyond the imagination of almost any human being. If the ethnic map of Bosnia-Herzegovina before the war had been called “a leopard’s skin,” now almost all of the leopard’s spots have been wiped out by ethnic cleansing. People who have lived in a (rural) area for years, don’t usually leave their birthplace gladly or easily. So how does a country’s map change so drastically? Hearing the answer, I understood why my friend called himself lucky. “You make people suffer to such an unbearable, excruciating extent, that they have no other option left except fleeing from their homes. Carefully and deliberately, you plot their utter destruction and inflict violence until they are mad with grief. You let fathers rape their sons, burn whole families alive in their houses, torture prisoners when holding them victim. Until people have nothing left to lose, nothing. War crimes are not an accident: they are the ultimate goal.”

When I asked at the end of the evening how he looked back on his childhood during the Bosnian war, my friend answered without hesitating: “It was one of the most valuable experiences of my life. Some people say that if the war would start again today, they couldn’t handle it and would go mad. I don’t agree with them. Two days. Two days is all it would take before I would turn the switch and go back into survival mode. It’s a skill you remember for the rest of your life.”

Text: Eva Corijn