At about 6pm on the 4th of August, a warehouse near Beirut ports, grain silos caught on fire and exploded. The damage was enormous, with over 7,000 people injured and nearly 200 people dead. Three months have passed since the explosions in Beirut rocked the city and the whole nation. The horrifying images of the shockwaves of the explosions and the carnage afterwards gathered sympathy around the world.

When one is beset by a tragedy, one usually chalks it up as a misfortune, an event beyond the actions of humans to stop. But the explosions in the port of Beirut and their underlying cause highlights the degree of corruption and incompetence that has made Libanon a dysfunctional state.

“Behind the Beirut explosion lies the lawless world of international shipping”

The explosions were caused by 2,750 tonnes of ammonium nitrate stored in a port warehouse and immediately questions started being asked as to why such an incendiary explosive was left to sit in a port right next to Beirut’s residential areas. The chronology of events are murky and complex but in a nutshell: In 2013 the cargo ship MV Rhosus set out to travel from Georgia to Mozambique, the ship was owned by a Russian, registered to a company listed in Bulgaria and “flagged” to Moldova. It was carrying ammonium nitrate. The owner forced the ship to make an additional stop in Beirut to pick up more cargo (in order to make more money) and while in Beirut it was impounded by the authorities for failing to pay port fees, among other things.

The ship’s owner Igor Grechushkin, realising that the ship was now costing him more than it was worth, filed for bankruptcy and abandoned the ship and its crew, leaving them stuck in Beirut without their wages. Incidentally the crew was “left aboard the ship, still carrying its explosive cargo, for almost a year, with no wages, no access to electronic communications and with dwindling food and fuel provisions.” In 2014 proceedings began to sell the ship, but with no buyers to be found, the ship was placed in a warehouse in a port of Beirut and left to sit there with its explosives for six years. While this disaster, according to Laleh Khalili, has its roots in a “global network of maritime capital and legal chicanery designed to protect businesses at any cost”, the disaster that is Lebanese politics is another story altogether.

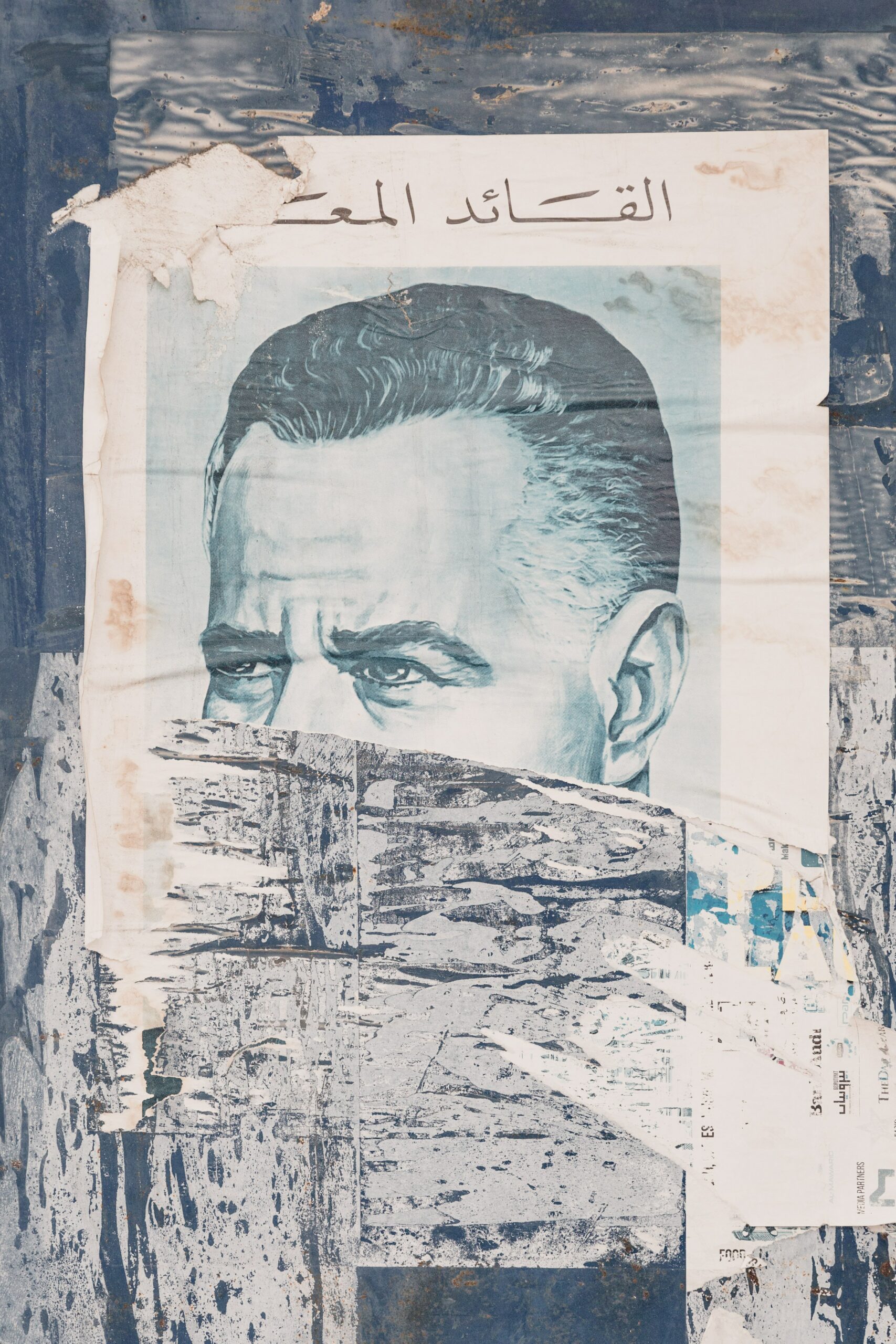

It’s a story of a corrupt and paralyzed system that cannot and will not change, where political posts are passed down from father to son, like family heirlooms. Politics in Lebanon is a family business and dominated by a few, the Gemayels, the Harriris, the Aouns, the Jumblatts, the Frangiehs. Take the Kataeb party for instance, a far-right nationalist party founded by Pierre Gemayel who sat in parliament for 24 years and whose two sons, Bachir and Amine, both were elected presidents. The grandson Pierre, also became a politician and is now a member of parliament. The same story occurred in other parties as well. “In the 1970s and 1980s, Amin Jumayyil (the Phalange Party), Dani Shamun (the National Liberal Party), and Walid Jumblatt (the Progressive Socialist Party) inherited their fathers’ political mantles”. The sons destined to carry the family name, continue the party legacy, and rule Lebanon in perpetuity.

It is a story of party bosses (Za’im) distributing political favors to the highest bidder and where voters are bribed to vote for each respective candidate. It is a story of a government that cannot and will not collect the trash because the party leaders keep fighting over which one of them gets to hand out the very profitable waste management contracts. In Beirut, the trash collection was until very recently handled by Sukleen, a company run by the business partner of Rafik Hariri (former president). The price it charged the government was four times the global average. Same goes with other public utilities, the country still suffers through electrical blackouts because certain parties stand to gain a lot more from handing out contracts to foreign companies than building new power plants.

The political scene is dominated by several major parties in Lebanon whose roots trace back to the brutal civil war that lasted from 1975 to 1990, parties like the Kataeb, the Marada movement, Hezbollah and the Progressive Socialist party all hail from militant groups that partook in the conflict.

To better understand modern Lebanon, a quick recap of the historical backdrop is necessary:

The current iteration of Lebanon was founded in 1920 by the French, in the aftermath of the first world war and the partitioning of the Ottoman Empire. The French ruled the country until 1943 when Lebanon was given its independence. The period of French rule was characterized by a divide-and-conquer strategy, which the colonial powers employed throughout the region, where the Christian Maronites in Lebanon were given preferential treatment over other groups, Sunni and Shi’a alike. The system of government put in place was called confessionalism, where seats in parliament were distributed along religious and sectarian lines, the Maronites were given ten seats, the Sunnis four, the Shiites two and the Druze one.

This type of government rule where political and institutional power is allocated along confessional lines was to be a permanent feature of Lebanese politics and civil life and it is the foundation of modern Lebanon, and according to some, the root of all of its problems today.

After the French left, this system became cemented with The National Pact “al-mithaq al-watani”, essentially an unwritten agreement between the dominant Maronite and Sunni communities outlining the basis of post-independence Lebanon. The stipulations of the agreement included that: The president always had to be Maronite, the prime minister a Sunni muslim, and the speaker of the parliament a Shia muslim. And furthermore there always had to be a ratio of 6:5 in favor of christians to muslims in the parliament. This political system and type of power-sharing is unique to Lebanon for the most part, Lebanon is what political scientist Melani Cammett calls “the example par excellence of a political system structured along explicitly sectarian lines”. Coincidentally when the Americans occupied Iraq after the 2003 invasion, the system they set up for the country post-Saddam Hussein was consciously modelled after Lebanon.

These communal and sectarian tensions, coupled with the fact that Lebanon is located in an area that has constantly been under geopolitical tensions. The Israel-Palestine dispute among other things, is what eventually led to the brutal Lebanese civil war (1975- 1990). Recounting the conflict and what led up to it is a difficult and complicated task with many different actors –both domestic and foreign – involved, needless to say it was a terrible conflict that devastated the country. Lebanon was invaded and occupied by Syria and Israel several times during the conflict. It ended with the signing of the Taif agreement, the deal brokered by Saudi Arabia.

The deal brought many changes and political reforms that were much needed, it adjusted quotas for seats in parliament giving christians and muslims an equal number of seats, but it left Lebanon’s overall system unchanged because although the deal “called for the gradual elimination of sectarianism as the basis for the regime, in practice it reinforced political sectarianism by continuing the system of sect-based power-sharing.”

Although the Taif agreement brought peace by and large the country has still been plagued by violence in the modern era. Syria, who had occupied parts of the country since the mid 70’s, did not leave the country until 2005. Lebanon is also a country where assassinations of politicians has become a regular feature of politics.

Financialisation run amok

Lebanon was never one of the wealthiest countries, but it was also never poor. Unlike its neighbors it does not have any oil reserves, although recent discoveries have suggested the presence of gas deposits but it is unlikely that it will lead to a significant boom of any kind. It never really experienced any proper industrialisation – like many countries in the third world – and it neglected agriculture and rural development leading to a weak and non-competitive agricultural sector.

Due to all these structural problems in their economy they have had to rely on their financial sector. Pursuing a form of rentier capitalism where they serve as a safe place where investors can deposit their money with no questions asked and with very lax, practically non-existent, regulations. Instead of building up an industrial sector or any kind of exportive industry they have relied on oil money from the Gulf States and remittances from the Lebanese diaspora to stay afloat.

Lebanon has had a fixed exchange rate (“peg”) against the US Dollar since 1997, at the rate 1507 Lira to USD. The Lebanese central bank had a mandate to make sure that this exchange rate would remain at the same parity no matter what would happen.

This policy made so that the country constantly needed dollars to pay for imports. Lebanon is a country which imports roughly 80% of what it consumes, and so they need to pay off their debts which are for the most part denominated in a foreign currency.

The central bank raised interest rates by an incredible amount (approximately 14% on Lebanese deposits and like 8% on dollar deposits, a lot more than you would ever get if you deposited your money in a bank in the US or Europe). This created an unbalanced economy which attracted huge capital inflows from the wealthy Lebanese diaspora living abroad, and people across the region looking to secure easy financial profits.

As long as the inflows from the wealthy Lebanese diaspora kept coming in, things were going great, but as soon as the flows stopped the economy grinded down to a halt. The financial crisis in 08-09´ and the Syrian civil war were all major factors in why the capital flows stopped coming in. Now the economy is in freefall, inflation is soaring and the Lebanese people can only withdraw 100-200 dollars a month tops from their own bank accounts, because the banks have imposed capital controls. Wealth inequality has increased dramatically in Lebanon in recent times, according to the Forbes 2020 rich list Lebanon has six billionaires living in the country, this is astonishing considering Lebanon only has a population of fewer than 5 million.

Disasters and demonstrations

Lebanon has suffered a series of disasters as of late, the explosions in August, the financial crisis and economic collapse, being especially hard hit by COVID-19.

It also cannot have escaped anyone’s attention that Lebanon, since last year, has been embroiled in protests and demonstrations. The protests in their scope and aim have been broad and aimed at the system as a whole.

The issues i have talked about in this article, the whole sectarian edifice which Lebanon is built upon and the financial crisis, are interlinked. The country’s non-existent welfare state has made people dependent on their sectarian and religious leaders for basic social services, further entrenching sectarianism in the country.

It is important not to lapse into victim blaming, while the problems are fully their own it would be shortsighted to overlook the fact that outside interests have played a key role in shaping modern Lebanon. Its status as an entrepôt and tax haven serves as useful for certain rentier interests, especially in the Gulf, as well as to the wider geopolitical interests of the US and its Middle East allies. The Lebanese people are stuck between a corrupt regime and outside neighbors who see it as a geopolitical playground.

The French writer Joseph de Maistre once said that “every nation gets the government it deserves”, one wonders then what the Lebanese must have done to deserve theirs.

Featured image by Marten Bjorke on Unsplash

Rine Mansouri

Writer for Utblick since autumn 2020