By Marine Khachatryan Originally posted October 22, 2018 at Enlight

Ara Güler, Armenian photographer living in Turkey, who got the name “The Eye of Istanbul”, died at the age of 90. Instead of mourning the death of another prominent Armenian, it is worth looking for the source of the greatness attributed to him in his photographs.

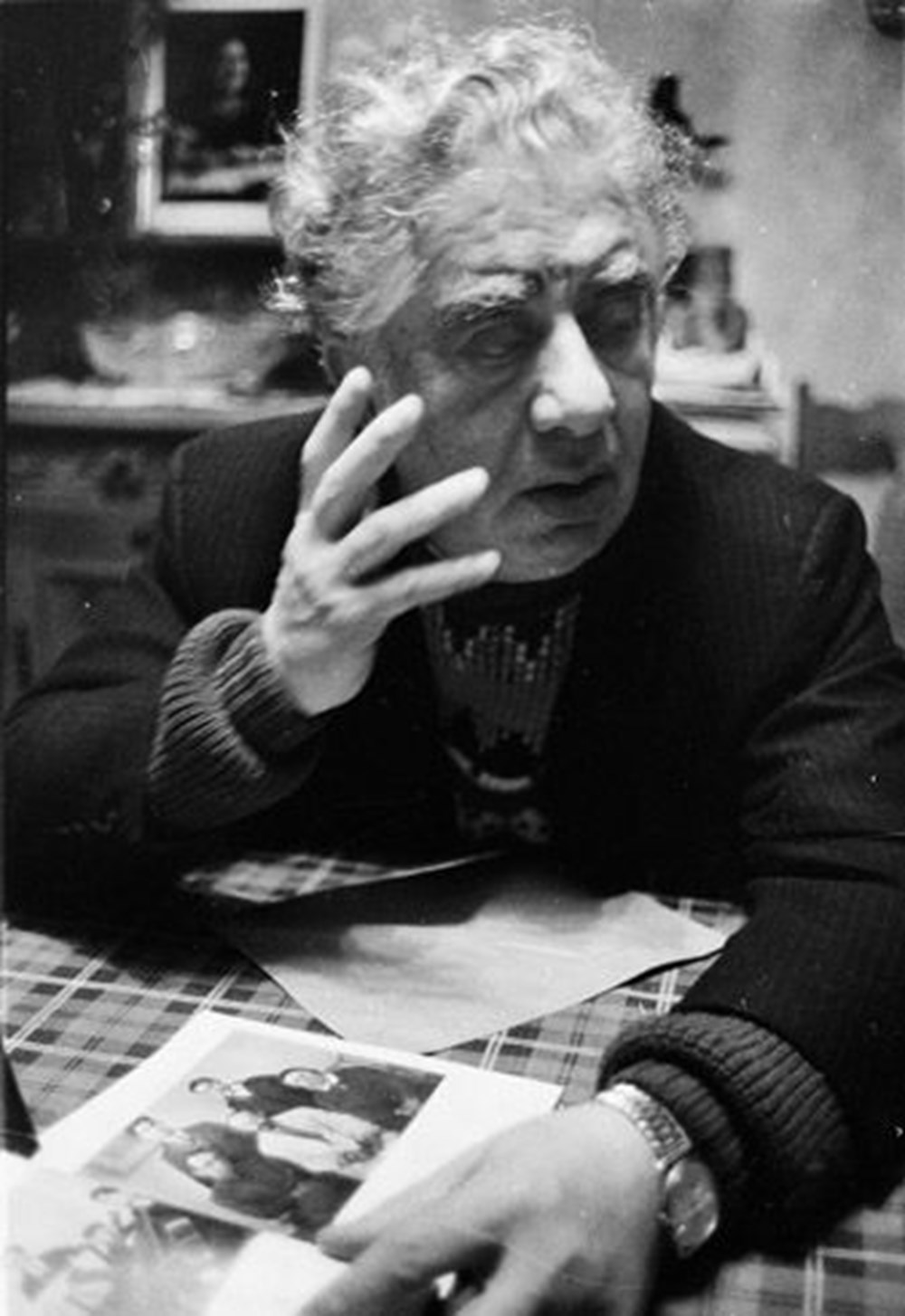

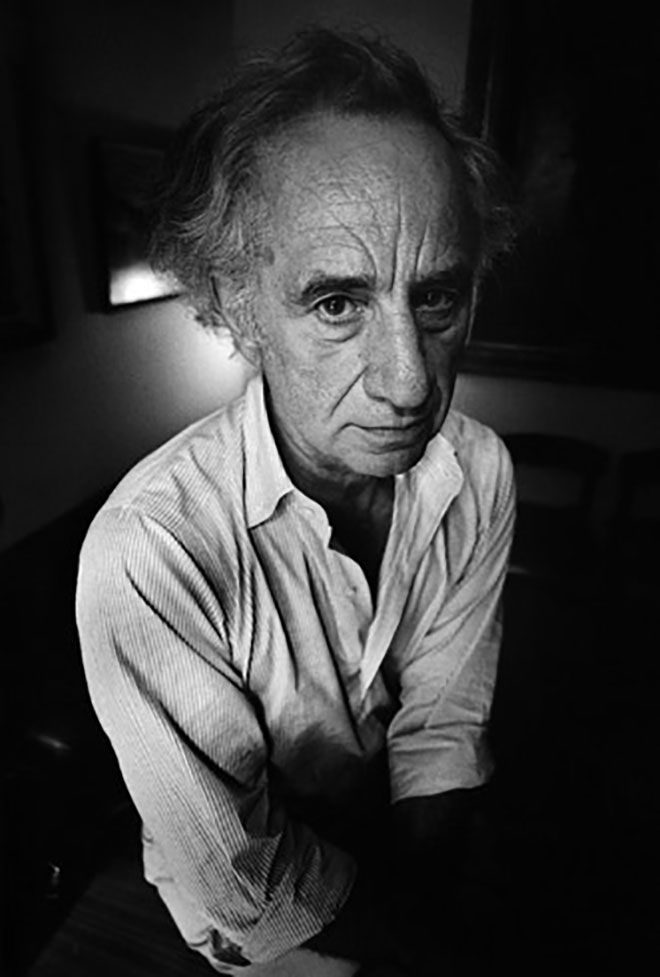

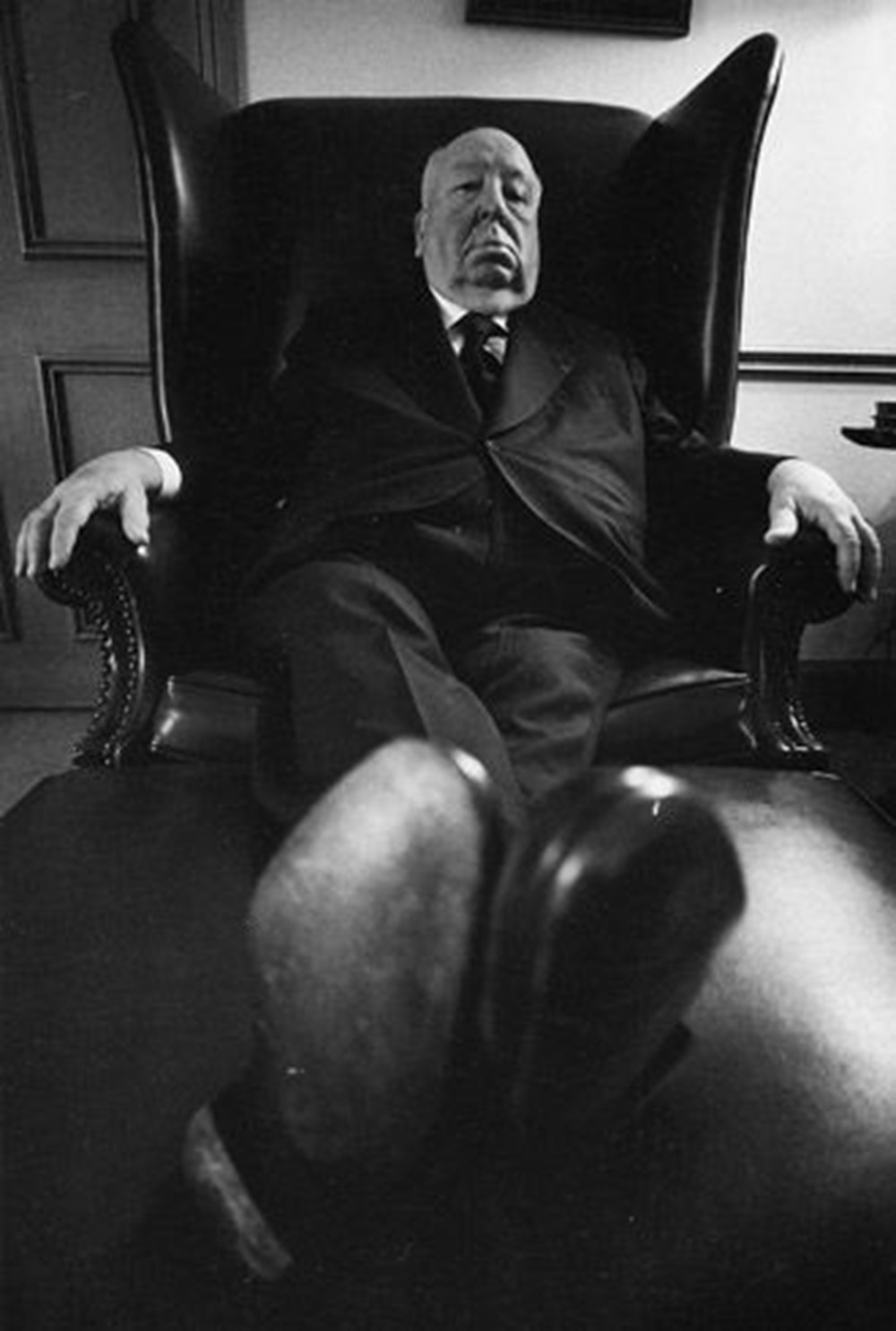

Photographs of famous people are not what makes this photographer great: his significance is not hidden there, even though the fact that he photographed Pablo Picasso, Winston Churchill, Orhan Pamuk, Indira Gandhi, Sophia Loren, Maria Callas, Alfred Hitchcock, Marc Chagall, Salvador Dali, Sergei Parajanov, William Saroyan and many others adds to the interest in him[1]. The value of his photographs is his way of examining these people, and with a sharp sense of “smell” catching their characteristics with almost childish enthusiasm. Composer Aram Khachaturian’s expressive fingers (as the part that creates music), director Elia Kazan’s shortened body and wide-angled forehead (as a sign of intellectual hard work), sculptor Alexander Calder’s body “sculpted” as if part of his sculpture, these are remarkable examples of Güler’s talent of capturing the characteristics best describing these figures in his photographs and drawing the viewer’s attention to them. And in Alfred Hitchcock’s “portrait”, like in a horror film, as a surprise to the foreground comes nothing less than the underside of the director’s shoe artificially enlarged. As if the tension of the horror films starts not from the screen of the cinema, but in the foreground of Güler’s this photograph, and in the background sitting calmly is the shoe’s: the horror’s author. This and other portraits make those photographed identical with their professions as the most distinctive part of their essence (as if Hitchcock is horror himself, Calder: the statue, Kazan: the mind, Khachaturian: the rhythm of his fingers.

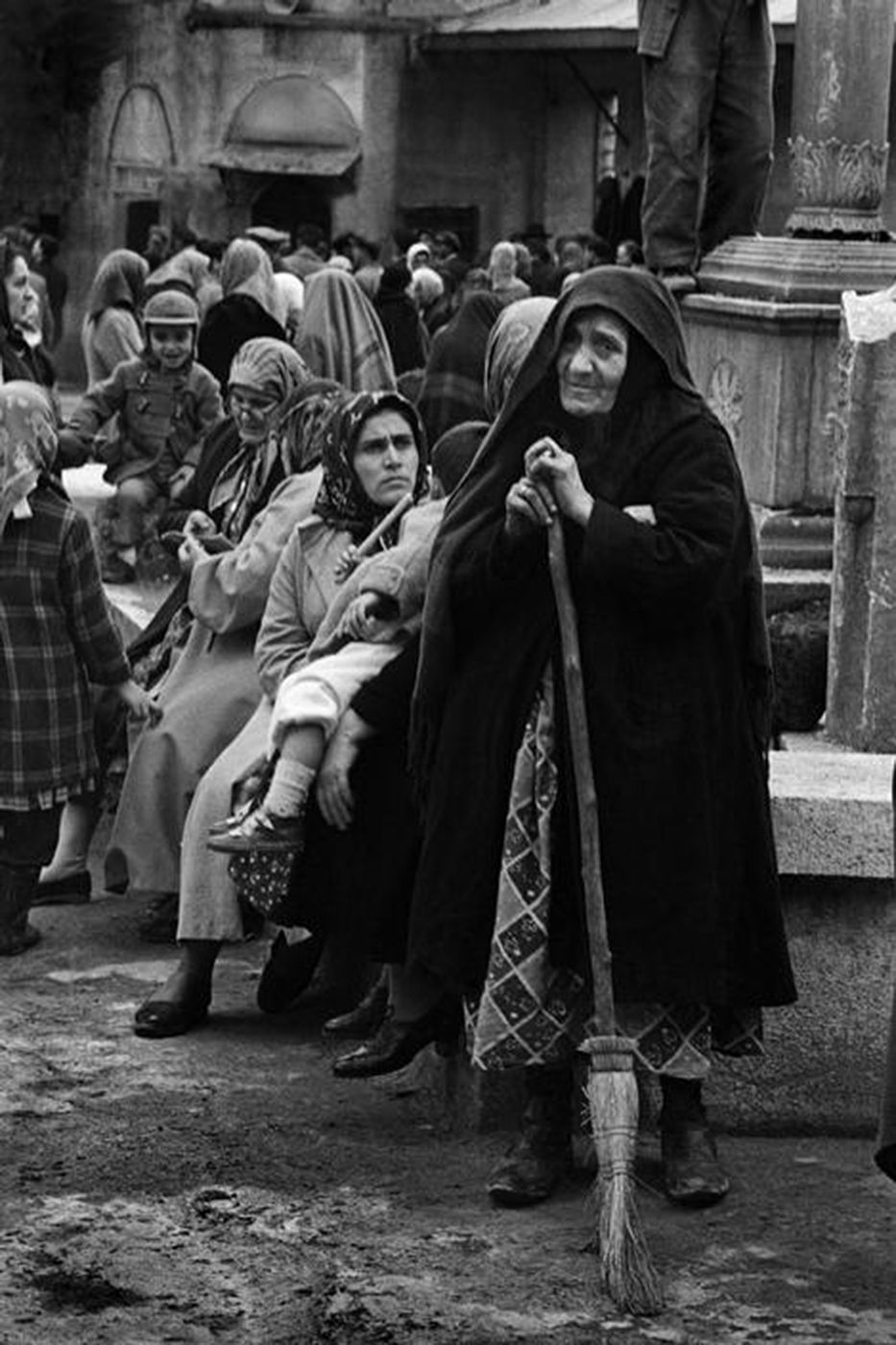

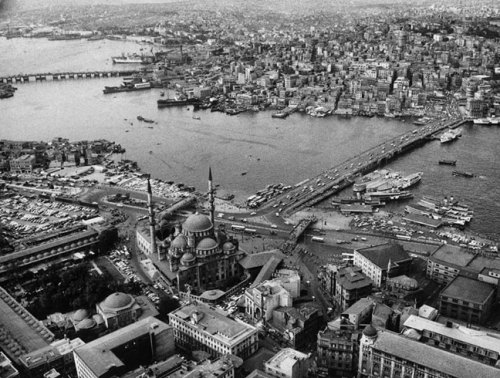

If in these photographs Güler was attracted to the person being photographed as long as it took for the dedication to become flesh and bone in his photograph, then Istanbul and its residents were his daily “weakness”. For Güler his birthplace Istanbul wasn’t a lifeless city, but one of the “heroes” of his portraits, the object of his love.

In his article “Camera Lucida” Roland Barthes writes that some photographs evoke in him only polite interest. The photographs in Istanbul first of all break the viewer’s politeness, the modest refusal to invade the life of the person being photographed, because politeness requires proper distance, and Güler deletes the distance between his heroes and the viewer, inviting the later into the life of the one being viewed with courtesy. The removal of that distance is what provides warm familiarity between the viewer and the one being viewed, which is why the residents of Istanbul seem heartily relatives, friendly conversationalists, with whose concerns and daily tasks he was communicating. That is the reason that Güler’s city photographs do not hide under the veil of impersonal and emotional neutrality, which is their attraction and charm.

One other attribute that unites the Istanbulian photographs is the presence and the movement of the people. Even in those photographs where there are no people, there is an item proving the presence of a human which showcases the photographer’s unlimited love towards the human being: the city for him is its residents in their hustle and bustle of urban life. Even the architecture in his photographs seems not to be fixed in the space but swims in the background of the general movement.

So, the eyes of Istanbul were closed but what those eyes saw and documented was preserved as one of the proficient ways to see the last century.

[1] In one of his interviews, Güler said that he likes to take pictures of urban scenes and ordinary residents of the city more than famous people.

Author: Marine Khachatryan © All rights are reserved.

Translator: Armine Avetisyan