The past decades have witnessed the rise of gender equality as a salient issue on the global political agenda. Tackled at different levels, it stands as a UN Sustainable Development Goal (SDG) and is mainstreamed through many channels. There is an increasing amount of nations which choose to position themselves as feminist states, notably through the promotion of gender equality in global affairs.

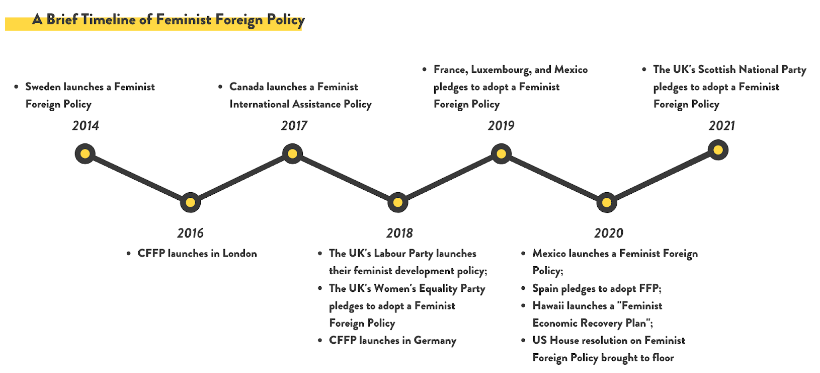

In 2014, Sweden’s then Minister for Foreign Affairs Margot Wallström pushed forward a groundbreaking type of foreign strategy: a Feminist Foreign Policy (FFP). As an actor that has pursued gender equality and human rights, both nationally and internationally, Sweden’s creation of an FFP illustrates itself in a norm diffusion process which is in terms of a soft power (the ability to use attraction and persuasion instead of coercion), similar to the one of the European Union (EU) which Sweden is a member state of.

So What Do We Mean by Feminist Foreign Policy?

As a foreign policy, it is a concept that calls for a state to promote values and good practices to achieve gender equality through diplomatic relations. Under the perspective of gender equality, we can understand FFP as a state’s engagement towards feminist practices through diplomatic paths. The International Center for Research on Women (ICRW) argues that “a feminist foreign policy is the policy of a state that defines its interaction with other states, as well as with movements and other non-state actors, in a manner that prioritizes peace, gender equality and environmental integrity, that enshrines the human rights of all”. Long-time due, it is a mechanism for equality, justice, solidarity and peace which encourages intersectional feminist perspective in policy-making.

Photo by Georges Toiansky on Unsplash

Following the footsteps of Sweden, other EU countries have sought to develop their own FFP. In 2018, Luxembourg released a strong plan which emphasised a feminist foreign policy across all streams of defence, diplomacy, and development. The same year, France published its « feminist diplomacy » objective, which places gender as a diplomatic priority. By announcing its commitment to implement a feminist foreign policy in 2021, Spain, after having joined the ‘FFP country club’, placed gender equality and empowerment of women at the centre of their foreign policy. More recently, both the UK and the Netherlands have announced their commitment to make gender equality a foreign policy matter by holding consultations on the development of national FFPs. At the EU level, the European Parliament (EP) in 2020 recommended an FFP calling for gender mainstreaming, protecting women’s rights, and promoting women’s equitable participation in conflict prevention and mediation. Many initiatives were later brought to life, with the purpose of developing government-apprehended policies as a response to the discrimination and systematic subordination that still characterises everyday life for countless women and girls across the globe (e.g. Biarritz Partnership for Gender Equality or the Global Network for FFP).

Furthermore, on the international level, countries such as Canada (Feminist International Assistance Policy, 2017), Mexico (Feminist Foreign Policy, 2020), and Lybia (Feminist Foreign Policy, 2021) have set their goals for their very own Feminist Foreign Policies.

(Source: Centre for Feminist Foreign Policy, 2021)

While these multilevel initiatives and commitments can only be applauded, one can wonder whether these FFPs are norm diffusion tools or a pure product of political branding. Norm diffusion is a practice that is well known and rooted in the DNA of many countries, notably in Western countries.

Norm diffusion is illustrated through the soft power of ideas, values, and norms which contrasts with the hard power (coercion) of the military and economy. Global transformations in world politics, economy, environment, conflicts, and societies have highly influenced the rise of the power of ideas and ideation in global politics. Normative power is intrinsically linked to the legitimacy of the promoted norms. As Member States of the EU, the mentioned FFP countries all share a spectrum of norms relating to different authorities that they are to promote in their diplomatic relations. This can for example take the form of added clauses in negotiations and agreements. Political branding is a concept that can be used here to counter the norm diffusion approach. It might be an approach that could be preferred when looking into the case of FFPs.

What Is Political Branding Though?

It is the critical use of traditional branding concepts, theories, and frameworks, transferred onto politics as a goal of differentiation from political competitors and identification between citizens and political entities. Political ideology matters for feminist politics and branding is indeed an effective way not only to create a political identity, but it is also a way to engage with salient contemporary issues.

A lot of criticism was raised regarding FFPs and the governments’ use of feminism as a political tool for branding. Indeed, while there is recognition for the intention of states to move from gender mainstreaming to more controversial politics through the FFP, the results are yet to be seen. Sweden’s mother FFP lacks overarching mechanisms to monitor the implementation of the FFP’s goals and objectives as well as coherent budgeting. And while France set up an accountability framework that allows to track progress, thus allowing for more transparency, the scope for action of French Feminist Diplomacy is rather limited, as it does not cover all areas of foreign policy such as trade, defence, and security. Moreover, it has failed to deliver its manual during its presidency of the Council of the EU, as was declared upon the release of its « feminist diplomacy ». The concept of a Feminist Foreign Policy can be considered a new and contemporary one. And while some states have declared their ambition to have it be a key dimension of their overall foreign policies, it is safe to assume that it is still a work in progress.

A big obstacle that should be considered is the lack of a common global definition of a feminist foreign policy. Indeed, this lack of definition paves the way for different interpretations and thus, different approaches and practices. Moreover, there are other issues, ranging from a lack of horizontal approaches to integrating gender-sensitive measures into policy-making to the (sometimes) inexistence of benchmarks, monitoring and resources. Unless such issues are addressed, fruitful results will not be observable and we will certainly not be able to talk in terms of norm diffusion. States need to tackle their credibility on the matter, and show their enthusiasm and commitment to their ambitions, as the contrary would only underline the use of feminism as a concept and of gender equality as a whole, as a tool for political branding.