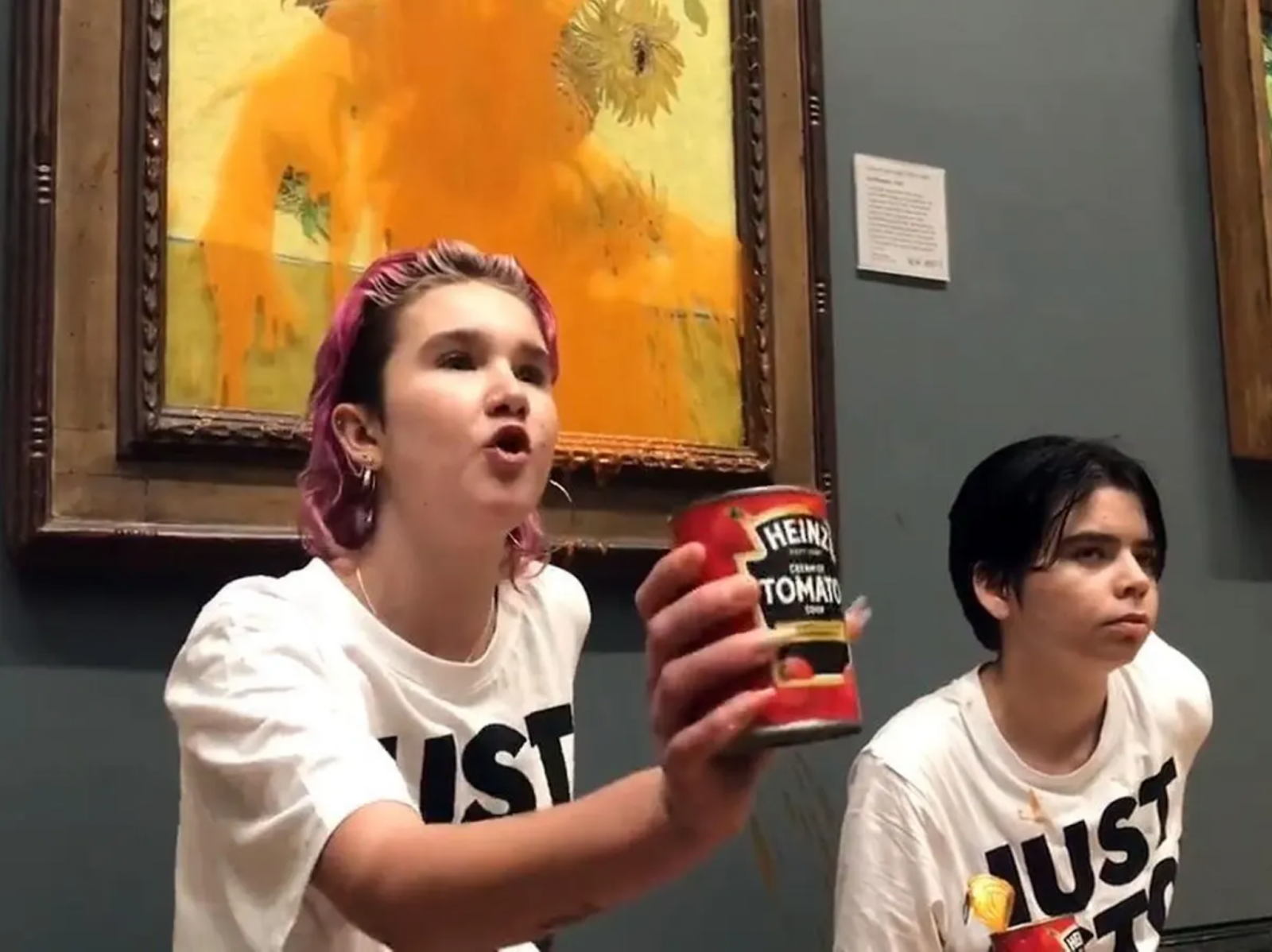

In October, activists from the organization “Just Stop Oil” got the whole world’s attention when they threw tomato soup on the famous painting “Sunflowers” by Van Gogh and glued themselves to the wall at the National Gallery in London. The purpose was to raise awareness towards their aim for the British government to end licensing and production of new oil and gas. Afterwards, there have been multiple incidents like the one in London, clearly inspired by the incident. For example in Germany protesters threw mashed potatoes on a painting by Claude Monet and in Italy, four activists splashed soup on a different Van Gogh painting. How does this kind of civil disobedience affect the public’s opinion, and what kind of impact does it make in the long run?

In a way, there is nothing sensational about a radical and controversial approach to environmental activism. For years, protesters have done stunts of all kinds with the aim of gaining attention and hopefully making a change towards a more sustainable future. Still, in an article published in Time magazine, Alejandro De La Garza writes about how the post-pandemic period has been characterized by a trend of “civil resistance” amongst climate activists. Some have focused on trying to physically stop polluting industries, like “Just Stop Oil” in the UK, others have aimed towards public disruption by making traffic jams. De La Garza also points out how most climate protests really have a short life in the public consciousness, if they get any media coverage at all. But the Van Gogh protest was different, as videos of the incident got millions of views and fired up a very heated debate online. So, how effective is the targeting of museum art pieces in a political communications perspective?

Public Opinion, Complex but Necessary

First, it is important to mention how it is an absolute necessity for a functioning public to have mutual communication between the people and the authorities. According to the book Makt, medier og politikk by Ihlen et al., free opinion formation must be integrated in the organization of society, and without it going beyond legal or political frameworks for acceptable expressions, citizens must be able to discuss issues together and public opinion to develop in a space independent of governmental and economic authorities. But a public like this also demands something from everyone involved. Ihlen et al. also express in their book the need for authorities to be able to facilitate a constructive social debate that is open to all, citizens must engage in issues that affect their position in society, and the media must function as a public meeting place, supplier of credible information and the public’s watchdog.

Public opinion is defined by Ihlen et al. in their book as the population’s attitudes in matters of general interest as it is expressed in an accessible way for most people. It is nevertheless pointed out that public opinion is a complex and diffuse concept; complex, because public opinion embraces cognitive processes at the individual level and collective processes at the societal level, and diffuse, because it lacks a defined content that is generally accepted across different social views and professional perspectives. Even though public opinion is shaped by processes linked to one’s own experiences and conversations, it is also essential to be able to have some insight into society’s opinion-forming processes to understand how society functions. McCombs et al. suggest that the continuous flow of news provides important guidance for the development of public opinion.

As society changes, so do the ways in which we communicate. Traditionally, the editor-controlled media has influenced public debate because they can set the agenda and the opportunity to determine the framework for interpretation. Brandtzæg believes that this influence has been increasingly weakened by algorithms today. The rise of social media has established the power of algorithms because many of the major platforms use algorithms for picking out information to show the users. Zuboff argues that Algorithms are governed by an “attention economy”, which has been criticized for operating with a logic that emphasizes user engagement to create growth.

Pushing Potential Allies Away

So, how is all of this relevant to throwing soup at famous paintings? In the aftermath of the incident, the activists from “Just Stop Oil” have gotten mixed feedback from the public, according to one of them in an interview with Reuters. On one hand, they have received praise for their courage to speak up and understanding of the paradox of people being upset about the chance of having an irreplaceable art piece destroyed forever but less uproar about the climate. On the other hand, people have called the activists out for protesting in a too violent manner. Despite a news cycle ruled by attention-fueled algorithms, public sympathy is also valuable for environmental activism and other political movements. If the groups are seen in a negative light, they could have their societal position, and therefore their influence, weakened. According to a survey conducted by climate professor Michael Mann among others, 46 percent of people said these kinds of tactics decreased their support or efforts to address climate change. Only 13 percent reported an increased support. “They are alienating potential allies in the climate battle”, Mann wrote. Public disobedience is defined as a criminal act, but “activists themselves are divided in interpreting civil disobedience either as a total philosophy of social change or as merely a tactic to be employed when the movement lacks other means.”

Time will tell how impactful the civil resistance from “Just Stop Oil” and other organizations will be, but it is clear it will be important to have the public’s favor in the resistance against climate change. Despite having attention from the whole world, it will be challenging to reach political change without sympathy from the public.