Despite many promising treaties putting forward equal pay for equal work ambitions, the gender pay gap (hereafter GPG) remains stubborn and systemic. The grounding principle introduced in the Treaty of Rome in 1957, followed by many others across the years, has laid a foundation for future gender-equal principles, notably in the workplace.

The gender pay gap accounts for the difference in average gross hourly earnings between men and women. It is calculated before the deduction of income tax and social security contributions. In the European Union (EU), the average gap in 2020 stood at 13%, even though it experiences strong variations across countries.

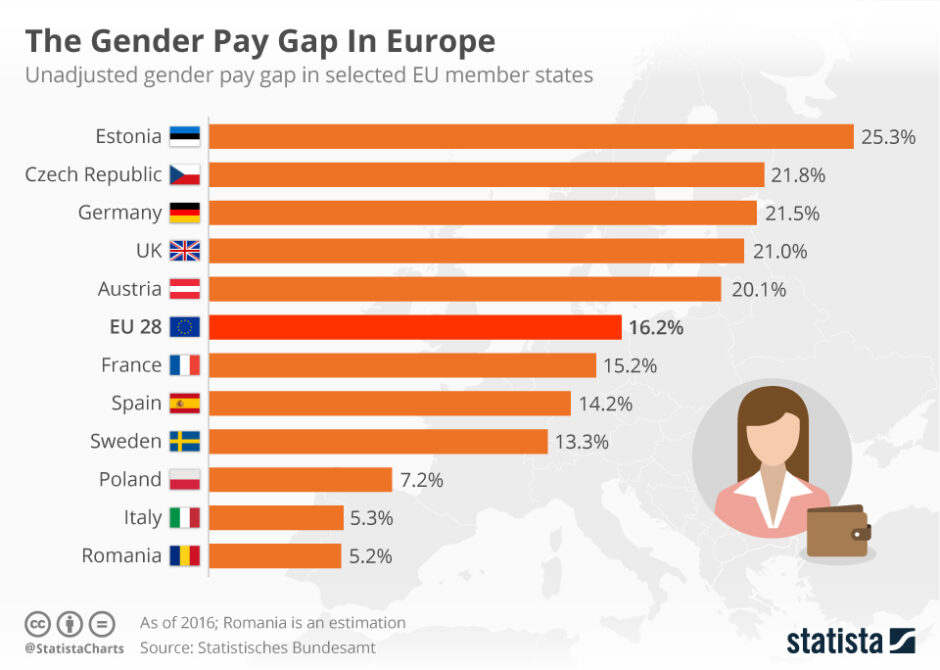

According to Statista, in 2020, countries such as Latvia (22,3%), Estonia (21,1%) and Austria (18,9%) were experiencing the highest GPG in the Union, while Luxembourg (0,7%), Romania (2,4%) and Slovenia (3,1%) stood as the top three countries with the lowest GPG.

Why do women earn less than men, sometimes to a great extent, even though pay discrimination is forbidden in the EU? Much academic work has been conducted over the years, with the aim of explaining the causes and mechanisms hiding behind this gap. Many reasons have been highlighted, ranging from structural imbalance to differences in the level of employment or education, and work experience. These reasons account for what is called the adjusted gender pay gap.

On the other hand, stands the unadjusted gender pay gap, which accounts for example for different career choices (notably influenced by family responsibilities), or for vertical and horizontal segregation. The two latter segregation types stand for the following: vertical segregation is the repartition of women in different hierarchical levels, notably in the managerial positions (commonly referred to as the “glass ceiling”) while horizontal segregation represents the over-representation of women in certain sectors, notably the low-paying ones. Many theories have spurred among scholars, as to what explains the unadjusted GPG, but what is certain is that it increases with age and throughout the career, most often alongside increasing family demands.

Indeed, the GPG remains relatively low when women enter the labor market but grows as women get older. This is notably problematic for future gaps in pension revenues, as women accumulate, save, and invest less than men and thus they are at greater risk of poverty at an older age. According to the EU, the gender pension gap was over 28% in 2020.

Closing the gender pay gap ranks high on the EU´s to-do list, and it is easy to understand why. On top of reducing gender inequalities and overall poverty linked to them, it would highly stimulate the economy and increase the gross domestic product as women would have more purchasing power, and thus the tax base would increase, letting some air in for the welfare systems to breathe.

In an ambition to uphold the principle of equal pay for equal work, and try to remedy the gender pay gap issue, the EU recently promoted and voted for a directive on pay transparency. Pay transparency is thought of by the EU, as a tool to contribute to closing the GPG, notably through a set of binding measures. Why pay transparency among other things? Scholars note that a lack of pay transparency can constitute a factor in strengthening the GPG, as it keeps women in the dark regarding possible discriminating practices exercised by management. While some EU countries such as Austria and Denmark have already tackled the issue by implementing pay-transparency policies, the great majority are falling behind. In this context, binding measures for all EU Member States (MS) seem to be necessary to enforce change in the union.

To establish a detailed portrayal of this new directive on pay transparency, let us describe the new measures. Employers will be obliged to declare the initial pay level to the future worker before employment, which aims to reduce the gender ask gap (meaning the gap between men and women in entry-level salary negotiations). An addition, the directive proposes that employers display the different criteria used to set and define the pay and career progression given to the worker. On the worker side, information regarding the individual pay level and average pay level for doing the same work or work of equal value will be made accessible to the workers and their representatives.

These measures will concern employers with at least one hundred employees, and enforcement mechanisms range from publicly sharing information regarding the GPG within the company (and by category of workers), to conducting a pay assessment in cases of a minimum of 5% pay gap in the company, and to the strengthening of existing minimum standards on sanctions in cases of infringements. Member States will be responsible for establishing the nature of penalties or fines applicable to infringements of national provisions. Overall, pay-transparency measures will enable workers to spot and challenge any gender discrimination, as well as raise awareness among employers to identify any possible discriminatory behaviors or gender bias in pay systems or job grading, as well as in salary negotiations. Pay transparency can seem to be a rather small action to take, especially when considering the size of the GPG issue. However, a wide range of indirect and direct effects can result from such a directive.

As previously mentioned, the EU’s directive on pay transparency will enable women to have access to information kept under secrecy, which might reveal discriminatory behaviors from the managerial staff. Having access to this information means that women will be able to either act upon these discriminatory practices or simply look for a job elsewhere. Women will undeniably gain more leverage.

Linked to this is the reshaping of women´s bargaining power, which will become greater in light of having access to pay information at the entry level, as well as during their careers, notably in situations of salary negotiations or while applying for superior positions within the company. This is highly relevant, as scholars note that women hold less bargaining power than their male counterparts, mostly due to societal and structural gender biases spurring from, for example, a gendered education system that encourages boys and girls to express themselves differently. This has notably been illustrated by a higher level of newly male graduates negotiating up to three times more than their female counterparts, because boys are more encouraged to speak up at school than girls.

In addition, pay transparency and bargaining power could positively impact women returning to work after their parental leave. Indeed, and as we previously mentioned, the gender pay gap is greater across the years, notably when motherhood becomes a part of a woman’s life trajectory. Once becoming mothers, women are more likely than men to be penalized at work, notably due to different personal investments in their roles, and due to a part of women switching to part-time work to accommodate their family responsibilities.

Overall, it is safe to say that women will contribute to pay transparency measures, and the EU framework gives the directive great strength, especially in terms of enforcement. While much has yet to be done, this move towards more equality is a hopeful one.