One of the most famous observations in political science is that the most democratic countries in the world also tend to be the richest, while the most autocratic countries also tend to be the poorest. In 1959 this observation led to one of the most influential theories in politics, Seymour Martin Lipset’s modernization theory. According to the modernization theory, economic development in countries should be associated with democratic development, as economic progress contributes to important aspects of democracy such as education and infrastructure. Although today the theory is much debated, a productive economy is still considered an important factor for democratic development. Because of this, one might think that petroleum rich countries more often than not should be amongst the most democratic countries in the world because of their great wealth. As we look at Norway and Canada, this is true. However, most of the time we see the opposite. The countries richest on petroleum actually tend to be amongst the most consolidated autocratic countries in the world. Venezuela, Saudi Arabia and Russia are just some of the examples that can be listed as representations of this phenomenon. While oil can be seen as one of the most powerful and beneficial resources a country can have, most citizens of oil rich countries still seem to suffer. Why is this? How can countries which seem to have the economic tools to thrive, also tend to have both amongst the poorest and most oppressed citizens in the world?

Michael Ross, a professor of political science at the University of California, has written the book “The Oil Curse”. In the book, Ross highlights the presented issue and explains the mechanisms behind the complex nature of oil wealth and democratic absence. Ross explains that oil wealth gives the rulers a lot of money for patronage. The wealth furthers the state’s influence. Influence which often overshadows the private sector while government jobs are also highly sought after, both which are key mechanisms to retain political loyalty. More money at the state’s disposal can also lead to better control over crucial institutions, such as the military and police which provide the state with a more firm grip on the citizens. Ross exemplifies the Arab spring to prove his point. The Arab spring was a democratic movement consisting of a series of protests and uprisings against regimes. The movement took place in northern Africa and the Arabian peninsula with the purpose of demanding more democracy as the vast majority of states were considered authoritarian or corrupt. Ross argues that states not “blessed” with a lot of oil were more responsive to the movement compared to states with a large oil production. Oil-states were more effective at beating down and restricting resistance because of their resources increasing their state capacity which could be used to constrain and dampen opposition.

Another important mechanism is that great wealth of oil also makes the state less dependent on taxes. According to Ross, taxes are an essential part to promote democracy. Less dependency on taxes takes away the people’s political participation. This is because when the people pay taxes it contributes to a greater demand of responsibility, hence making the government more accountable. Without the taxes, the demand and pressure on the state decreases, making it easier for those in power to stay in power.

Ross even claims that gender inequality in the Middle East is sprung from the oil curse. A common perception is that Middle Eastern countries have less gender equality than much of the rest of the world because of cultural circumstances. Ross argues that culture is only a small part which is fueled and amplified by the oil profits in these countries. This is because oil tends to benefit male dominated industries while sectors dominated by women tend not to witness the benefits from the supply, something which consequently restrains women in oil-dependent states while elevating men’s position in society.

To conclude Ross’ theory, though oil rich countries tend to have some of the poorest citizens, certainly someone benefits from the supply, this just tends to not be the people, but the governments. Ross’ theory is based on the thesis that governments in oil rich countries benefit more without democracy than with it. The profits from oil thus increases the state’s capacity to control the people and rule without their consent. In other words, governments benefit so greatly that they can use the profits to elevate their power and keep their authority.

The oil curse is just as all other theories regarding social sciences not a law of nature in the meaning that exceptions do occur, Norway being the most eminent instance of these exceptions. The country is much dependent on oil, still, they are one of the most consolidated and prosperous democracies in the world. This is probably because of Norway’s early transition toward democracy accompanied by a number of other theories in political science explaining democratization and democracy. However, these explanations and few exceptions are irrelevant to our issue, as the pattern of oil and autocracy is still strong. There are always exceptions in political science and explanations for why these are. Regardless, the necessary element to note is that exceptions don’t have to make a theory irrelevant, it simply makes the puzzle more complex.

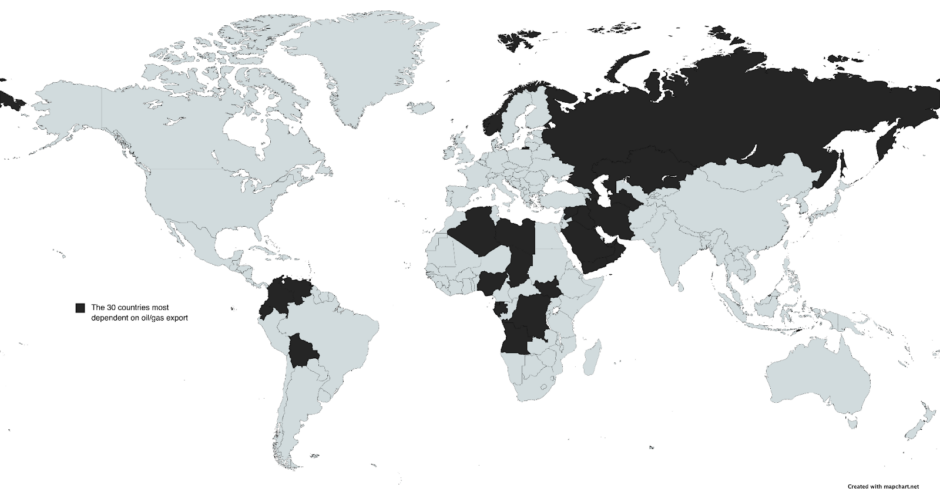

To demonstrate this pattern of oil and democratic absence, the map illustrated below shows the top 30 most oil and gas dependent countries in the world, that is, the countries in the world whose economies are most centralized around oil.

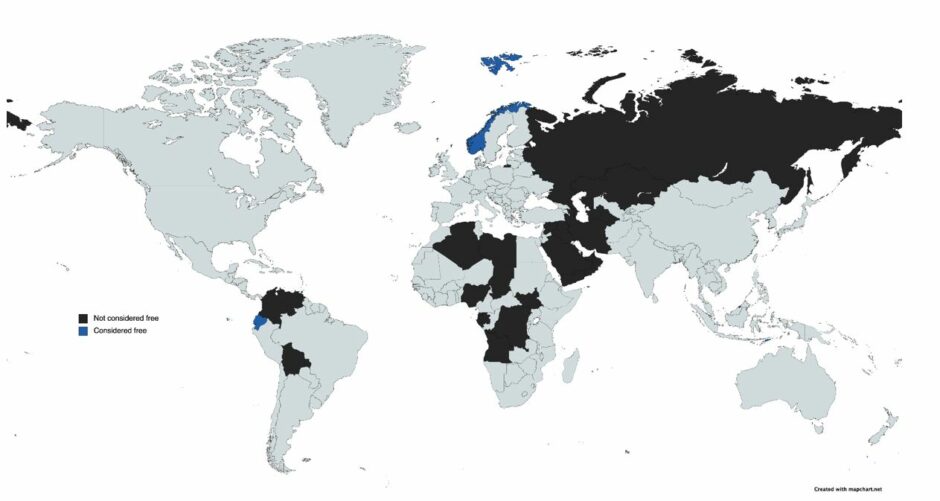

The second map shows the same countries, except the ones in blue are considered as “free” by FreedomHouse, a good indication to determine a country’s democratic condition.

The map undeniably demonstrates the pattern of oil dependent countries and the lack of democracy.

Besides Ross’ theory, states with deficient or rather non-existent democracy accompanied by possessions of large oil reserves could also be hard to democratize by intervening with financial tools. For example, financial tools such as sanctions, could put pressure on undemocratic states to reform policies, hence supporting growth of democracy. But, when states obtain large quantities of oil, their dependency of foreign cooperation decreases as oil is a reliable source for great wealth. As the dependency decreases the regime’s latitude to suppress and implement undemocratic policies increase, which consolidates their power further.

The greatest threat to human existence and the most predominant challenge today is climate change. Thus, the threat to our existence has brought the shift toward renewable energy on the top of the agenda for numerous oil consuming countries. Countries, which as of today, are important customers for the oil-states. Therefore, the shift toward more green energy sources will greatly impact the states dependent on oil and gas. As countries move away from the usage of oil to find alternative sources of energy this will mean more excess in the states which provide themselves through oil. The excess will in turn cause decline in the states capacity, eroding the aggrandizement of regimes in power.

Ross suggests that this erosion of those in power could lead to two different outcomes. One outcome of regimes losing their power is that it could potentially lead to instability. This type of instability has been seen in many cases throughout history and isn’t usually very pretty. The other outcome, according to Ross, could be that the erosion results in more democracy. As the regime falls, it could potentially lead to democratic reforms and broader distribution amongst sources of income. A more diversified economy would then, perhaps, break the curse, forcing states to turn oil into an asset instead of a reliance, similar to the US. If this would be the case, not only would a shift to renewable energy be beneficial for the climate, but also democracy.

It seems that petroleum is not always a blessing, but sometimes rather a curse. Regardless of whether petroleum is a curse or not, and which one of Ross’ two possible outcomes turns out to be true, the shift from oil toward more “green energy” is inevitable. Therefore, one can only hope that the shift will also lead to more democracy and equality rather than instability and turmoil. The shift to renewable energy is dramatic for numerous reasons, I argue this is one of them. A shift toward not only green, but perhaps even democratic and equal energy.